By Monica Corona

Director of Inclusion and Sustainable Development

and Carmen Paola Avilés (intern)

Both in Ethos Innovation in Public Policies

Domestic work in Mexico has historically been a paradigm of job insecurity. Nine out of 10 people who work in this sector are women, constantly exposed to exploitation and unfair working conditions. In this context, domestic workers in Mexico have been fighting for years for full recognition of their labor rights and effective access to social security, fundamental aspects for decent work with fair wages and benefits. What has changed?

Although reforms were implemented in 2019 to guarantee their labor rights and incorporate them into formal employment through registration with the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), progress has not continued due to state inertia and the reluctance of a significant number of employers. The mere existence of a legal framework is insufficient; proactive state participation is needed to consolidate enrollment efforts through dignified campaigns and concrete incentives that ensure these workers' effective access to social security, thus guaranteeing decent and secure work.

Data from the National Survey of Occupation and Employment (ENOE) of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), published in 2024, allow us to observe the severity of the problem: 2.5 million people aged 15 and over were employed as paid domestic workers in Mexican homes. Of these, 9 out of 10 were women. Of these, 96.31% of those employed were informal workers, while 83.41% of men were employed in this capacity.

Housework ("domestic work," as it is also known) has historically been delegated to women due to the concepts, stereotypes, and gender roles that exist in our society. It is conceived—even in the case of paid domestic workers, that is, those employed by an employer—as an "act of care."

This misinterpretation leads to a distortion of the existing (labor) relationship, viewing paid domestic work as not a formal employment relationship in which workers provide these services. This distorted understanding encourages the normalization of verbal agreements, based on a supposed "trust," which, in practice, exempts them from fulfilling basic labor obligations. Thus, although this work contributes to the well-being of millions of Mexican families, a vast majority of domestic workers in Mexico do so at the expense of their own well-being and that of their families.

Let's take a scenario: the case of Aurora, a domestic worker without a written contract or social security, who works in a private home under a verbal agreement. One day, her three-year-old daughter becomes seriously ill, and the relative who usually helps care for her is unavailable. Aurora requests a leave of absence, and her employer agrees, as a "gesture of humanity." Without social security or income for days missed, Aurora cannot cover her medical expenses or buy medication. Desperate, she turns to a relative for a loan so she can care for her daughter.

Aurora's case reflects the reality of thousands of women in Mexico, who are engaged in precarious jobs and in a position of extreme vulnerability. The alarming figure of 96.31 million women employed in this sector without a written contract is a stark indicator of the prevailing informality. Of this population, one in three female domestic workers supports her family and dependents while enduring informal, poorly paid employment conditions without access to social security. This double burden—economic and caregiving—is compounded by the lack of benefits that could help alleviate it, such as childcare and medical care.

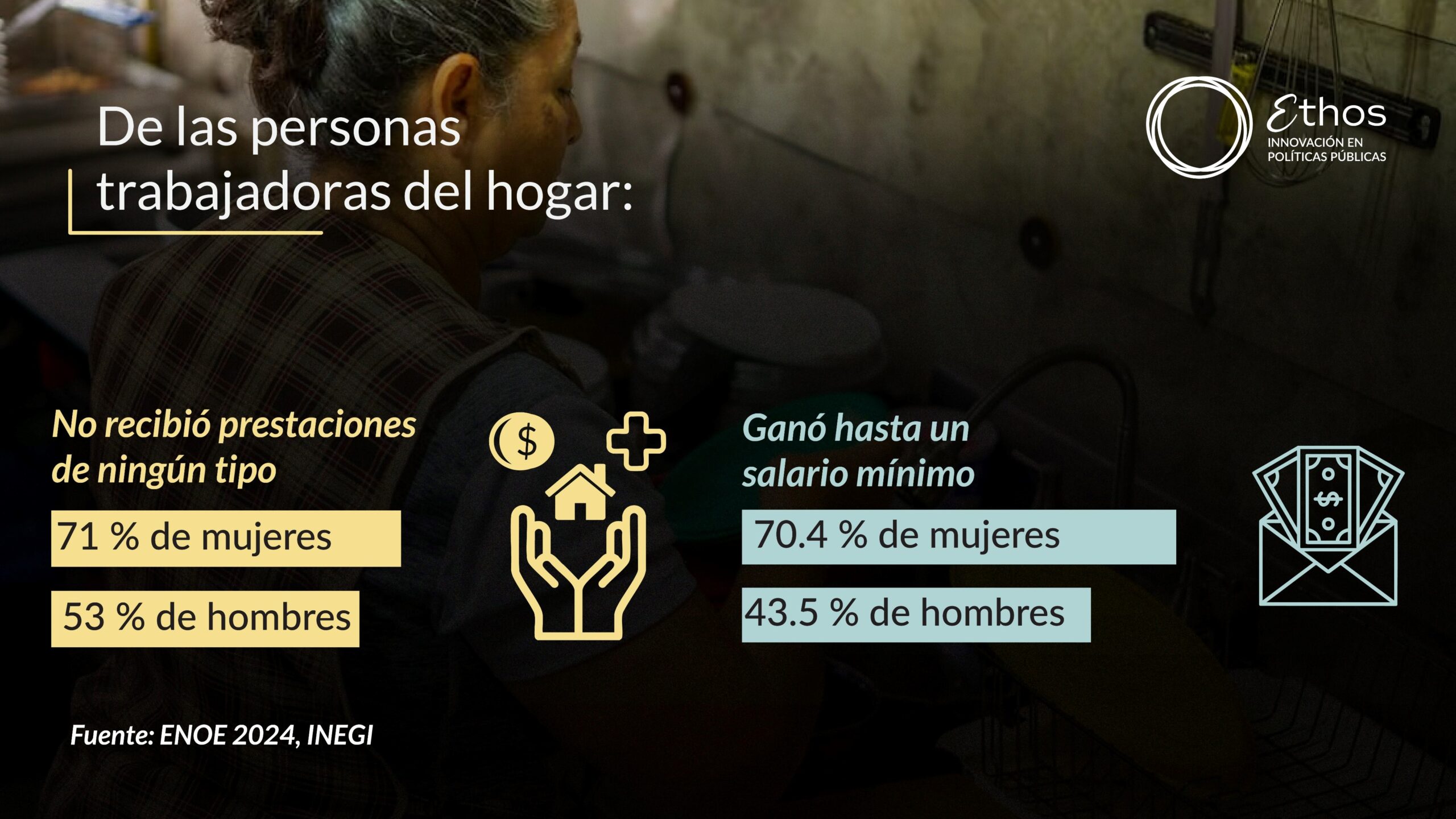

Job insecurity in this area also has a marked gender bias. The data is eloquent: female domestic workers receive lower wages and fewer benefits than their male counterparts. Data from the National Employment Organization (ENOE) show that 711,000 women received no benefits at all, compared to 531,000 men who did not; 70.41% of women earned up to one minimum wage, compared to 43.51% of men who earned up to one minimum wage; furthermore, almost 231,000 women earned between one and two minimum wages, compared to 371,000 men. Even within the same precarious sector, where the majority are women, women still earn less! Gender inequality remains prevalent in the most vulnerable sectors of the labor market.

Mexico has addressed this issue by ratifying ILO International Convention 189 and reforming the Federal Labor Law (LFT) and the Social Security Law (LSS). The IMSS pilot program, launched in 2019, was also an essential step. However, initially, the Social Security Law considered the affiliation of paid domestic workers a voluntary process, prolonging their exclusion from the social security system. It wasn't until 2022 that it became mandatory for employers to enroll them. Although this represented significant progress, to date it remains only the beginning of a process that requires greater decisiveness. Addressing the deep sociocultural inequalities and discriminatory prejudices that impede progress and the enjoyment of their rights to work with dignity and free from discrimination remains a pending issue.

The historical and societal debt owed to paid domestic workers is considerable. We need to go beyond mere declarations and implement concrete actions. It is our collective responsibility to ensure that those who sustain the well-being of countless households enjoy the same rights and dignity as any other worker. A contract, social security, and a fair wage are not concessions or privileges, but fundamental rights that must be guaranteed.

NOTE: Article originally published in Animal Político (July 12, 2025). Retrieved from https://www.ethos.org.mx/inclusion/columnas/urge_dignificar_el_trabajo_del_hogar_remunerado_y_el_acceso_efectivo_a_la_seguridad_social